Icons: Eli Keszler in Conversation with Adam Curtis

23rd June 2021

Photography Leia Jospe

Design Dominic Flannigan

To commemorate the release of his new album, Eli spoke to the celebrated BBC journalist and documentarian Adam Curtis in Spring 2021

Keszler: Your latest docuseries, Can’t Get You Out of My Head, is subtitled “an emotional history of the modern world.” This really struck me because you’d think emotion would be incompatible with history, accurate or not. Yet at this moment, it makes perfect sense why you’d suggest that connection. We do seem swayed from every angle by emotion rather than fact. Political history has become more subjective and abstracted. Do you feel that our age is best understood on an emotional register, and if so how does the music and culture of the time reflect it? Curtis: I think that we live in a time in which the idea of the individual self has become the dominant idea and guiding force. Throughout the west - and in many other parts of the world - people believe that what they feel, what they desire and what they dream of is the most important thing in the world. I made a series called The Century of the Self that traced the rise of this idea. How it was born out of a revolt against old patrician ideas that you should do what the elites told you to do - because they knew best. At the heart of the revolt was a belief that this old form of control repressed the true authenticity of your feelings. That really the thing to trust was what you felt inside - because that was true. In the films I show out of that came a glorious new radicalism - but also how modern consumer capitalism saw something in that. They realised that the key belief in this new age was not only the desire to be yourself, but also to express yourself. Most people though didn’t have the tools to do this - and consumer capitalism stepped into that gap and offered people a myriad of objects and styles - and music - through which they could tell the world about those feelings inside them. Then that spread to politics. And I thought that if you want to do a history of this age then it has to be as much about what went on inside individual’s heads - about their feelings - as about the world outside. Because they - and their interaction with the real world are what shapes large parts of today’s reality.

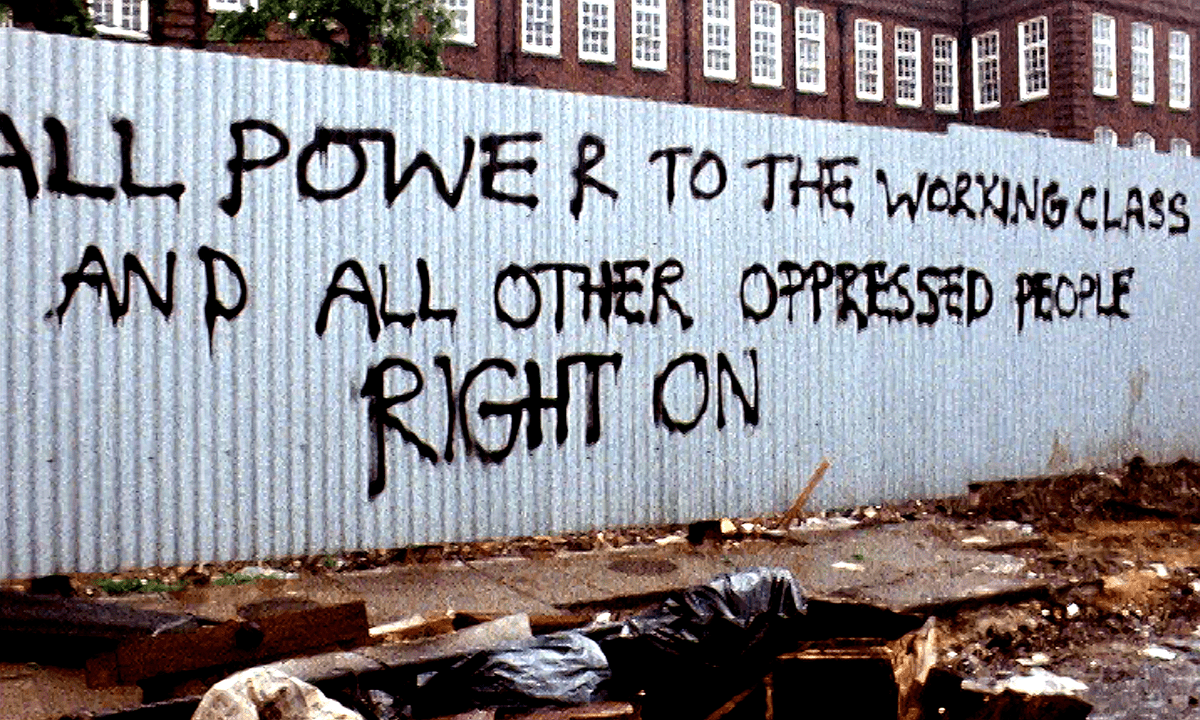

It seems like art and music are more readily weaponized for political purposes than capable of articulating a radical politics themselves. Similarly, to my mind, political art often seems to confuse categories and misallocate its strengths. Meaning and symbol seem to be somewhat inverted now. I’m thinking, for instance, of Trump playing The Rolling Stones’ ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’ during his acceptance speech or using REM’s ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It’ on the campaign trail. There was some brilliant irony at play in his use of music to troll his opponents and wink at his supporters. How do you think the relationship between culture and politics has changed? Has art ever been able to articulate a radical politics or is that a convenient story we tell ourselves to anchor our critiques of the time? The age of the individual was glorious because it liberated millions of people from having to bow down to the patronising and hypocritical elites. But it also had a very strange effect on radical politics. Because if you believed that the most important thing was what you felt inside - then you didn’t want to join a political party, or a trades union, or even a radical political movement because they would tell you what to do, and you would have to surrender that precious “you” to the demands of the group. But many people - for the best of reasons - still wanted to be radical and to change the world for the better. They found the solution in the idea of “radical” art - because it allowed you to express your radicalism as an individual and not be compromised as a free self. Out of that came some wonderful art and music from the 1970s onwards - but the downside was that the old engine of radical change, the collective power of the people, disappeared. And the sad fact that shows this, is that during that time the politics of the western societies shifted sharply to the right. That new expressive radicalism failed to stop Reagan, Thatcher, the rise of a corrupted financialized system of debt and control, and the Iraq invasion. That’s not to say that the art and music wasn’t good - much of it was fantastic, and it did express beautifully and very powerfully the new freedom and confidence that emerged in the women’ movement and the gay rights movement - and also revealed the anger and the brutality and violence that was repressing black communities. But somehow it became a sealed-off area where all that could be expressed, yet because collective power had disappeared it couldn’t take the next step and change the underlying structure of control in those societies. I think people have now realised that - and movements like Black Lives Matter and Me Too and the Green New Deal are beginning to reawaken a collective power - and are talking about how it is necessary to change the structure of power. It’s good.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In The Birth and Death of Cool, music critic Ted Gioa talks about the history of cool as a concept, one which came out of the jazz scene and came to define the postwar era. His claim is that coolness emerged in response to the stability of the postwar period but is now in decline. My hunch for why this happened has to do with the gradual mainstreaming of fringe subcultures, already underway in the sixties’ experimentation with radicalism and seventies’ retreat into spiritualism. Do you see a cultural tone that defines our time? I agree with Ted Gioa - I think it is a very good book - that the idea of cool has become decayed and corrupted. As he says - its roots lie in the jazz of the 1940s and 1950s, but what is fascinating is how it was then picked up by the new white radicals. There was a very important piece written by Norman Mailer at the end of the 1950s called The White Negro - where he described how a new white bohemian class were adopting the stance of cool as a way of standing outside their society which they saw as corrupt and compromised. But, as Gioa says, the original politics of that fell away and cool became a posture of ironic detachment from society in which you could express your unique individuality through that coolness. And I think that posture - which became very dominant during the 1980s and 90s in response to the rise of Reagan - turned into one of the forces holding back a new way of seeing the world that would really engage with the growing inequalities and racism. You just liked to watch from outside as it were. I do think - and hope - that a new mood of engagement will rise up to replace it. There are signs of that - but I don’t think anyone knows what the defining tone of this time is. That’s what makes it so fascinating. We don’t seem to have the language to describe what is happening. That’s why we need a new kind of journalism - to do that.

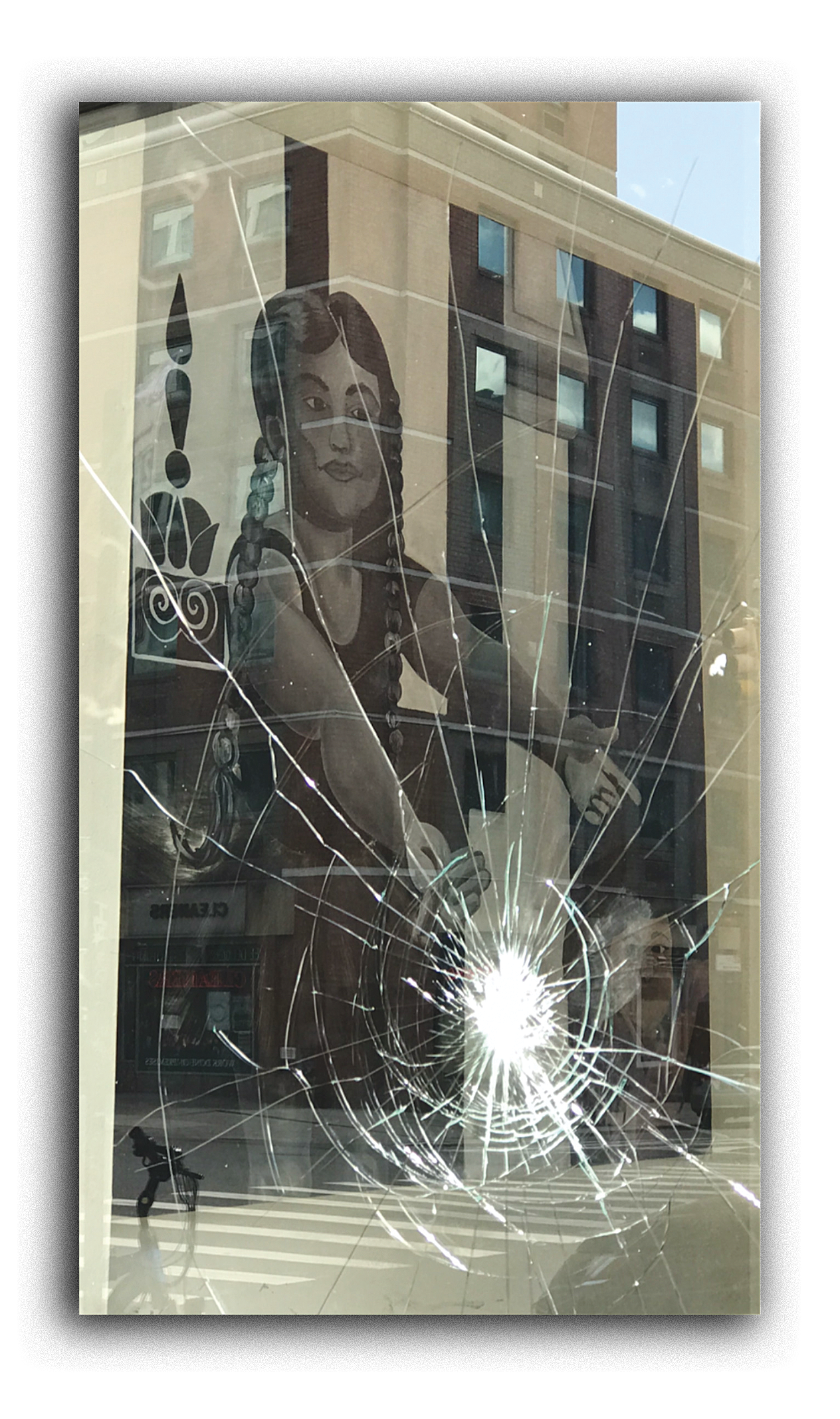

During the start of the lockdown I spent many nights walking around the empty streets of Manhattan and recording audio that would eventually become material for my record. There was something surreal, unnerving and beautiful about the silence on the street. The infrastructure of the city was exposed and sounds from blocks away suddenly became audible in a way they normally wouldn’t be. Do you think the last year has revealed an aspect of the world we were not aware of, or just reinforced something we knew was always there? Over the past twenty years we have lived through a number of catastrophes - starting with 2001, then the Iraq Invasion, the global economic crash, Trump and Brexit - and now Covid. I think the problem is that they came at a time when all politicians - from both left and right - had given up on giving you positive visions of the future. Instead they just promised to keep things stable. It meant that when the catastrophes hit it seemed to confirm the lurking idea that the future will always be dark and frightening because there was nothing positive to counter it with. And out of that came a dark pessimism - a feeling of inevitability. That there is little governments can do to stop the bad stuff. I have a hope that the experience of Covid may change that - because in both Britain and America collective action and the extraordinary achievements of modern science have shown that you may be able to solve the crisis. And out of that may come a new broader idea that we can change the world for the better. That said though - what the crisis has also revealed is the extraordinary inequality between the rich western societies and much of the developing world. The horror of what is happening in India and Brazil will have effects that we cannot predict. But they may also lead to a realisation that that relationship between the different societies across the world should also change. I hope.

I wanted to ask you about the way you use music to create contradiction or counterbalance in your films. You’ll often use an upbeat pop song to offset ominous, violent or otherwise disturbing footage. I often think about this relationship within a piece of music itself, and applied this principle quite a bit on the new record. What about this tension makes it so immediately and incredibly potent? I’m wondering about your process in designing your soundtracks? I always have a problem when film makers use music in a literal way. Pink Floyd’s Money to illustrate Bankers and greed for example. I look to music to do something different - to create a mood that helps people look differently at the stories and events I am narrating. And that often works by using music that surprises. Film and TV has become very rigid in the different forms of films it makes - so the viewer is very used to those forms - I think I try and sometimes fight against those expectations by surprising you with a song that expresses the mood I am trying to create but also makes you look with fresh eyes at the story.

It seems like art and music are more readily weaponized for political purposes than capable of articulating a radical politics themselves. Similarly, to my mind, political art often seems to confuse categories and misallocate its strengths. Meaning and symbol seem to be somewhat inverted now. I’m thinking, for instance, of Trump playing The Rolling Stones’ ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’ during his acceptance speech or using REM’s ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It’ on the campaign trail. There was some brilliant irony at play in his use of music to troll his opponents and wink at his supporters. How do you think the relationship between culture and politics has changed? Has art ever been able to articulate a radical politics or is that a convenient story we tell ourselves to anchor our critiques of the time? The age of the individual was glorious because it liberated millions of people from having to bow down to the patronising and hypocritical elites. But it also had a very strange effect on radical politics. Because if you believed that the most important thing was what you felt inside - then you didn’t want to join a political party, or a trades union, or even a radical political movement because they would tell you what to do, and you would have to surrender that precious “you” to the demands of the group. But many people - for the best of reasons - still wanted to be radical and to change the world for the better. They found the solution in the idea of “radical” art - because it allowed you to express your radicalism as an individual and not be compromised as a free self. Out of that came some wonderful art and music from the 1970s onwards - but the downside was that the old engine of radical change, the collective power of the people, disappeared. And the sad fact that shows this, is that during that time the politics of the western societies shifted sharply to the right. That new expressive radicalism failed to stop Reagan, Thatcher, the rise of a corrupted financialized system of debt and control, and the Iraq invasion. That’s not to say that the art and music wasn’t good - much of it was fantastic, and it did express beautifully and very powerfully the new freedom and confidence that emerged in the women’ movement and the gay rights movement - and also revealed the anger and the brutality and violence that was repressing black communities. But somehow it became a sealed-off area where all that could be expressed, yet because collective power had disappeared it couldn’t take the next step and change the underlying structure of control in those societies. I think people have now realised that - and movements like Black Lives Matter and Me Too and the Green New Deal are beginning to reawaken a collective power - and are talking about how it is necessary to change the structure of power. It’s good.

In The Birth and Death of Cool, music critic Ted Gioa talks about the history of cool as a concept, one which came out of the jazz scene and came to define the postwar era. His claim is that coolness emerged in response to the stability of the postwar period but is now in decline. My hunch for why this happened has to do with the gradual mainstreaming of fringe subcultures, already underway in the sixties’ experimentation with radicalism and seventies’ retreat into spiritualism. Do you see a cultural tone that defines our time? I agree with Ted Gioa - I think it is a very good book - that the idea of cool has become decayed and corrupted. As he says - its roots lie in the jazz of the 1940s and 1950s, but what is fascinating is how it was then picked up by the new white radicals. There was a very important piece written by Norman Mailer at the end of the 1950s called The White Negro - where he described how a new white bohemian class were adopting the stance of cool as a way of standing outside their society which they saw as corrupt and compromised. But, as Gioa says, the original politics of that fell away and cool became a posture of ironic detachment from society in which you could express your unique individuality through that coolness. And I think that posture - which became very dominant during the 1980s and 90s in response to the rise of Reagan - turned into one of the forces holding back a new way of seeing the world that would really engage with the growing inequalities and racism. You just liked to watch from outside as it were. I do think - and hope - that a new mood of engagement will rise up to replace it. There are signs of that - but I don’t think anyone knows what the defining tone of this time is. That’s what makes it so fascinating. We don’t seem to have the language to describe what is happening. That’s why we need a new kind of journalism - to do that.

During the start of the lockdown I spent many nights walking around the empty streets of Manhattan and recording audio that would eventually become material for my record. There was something surreal, unnerving and beautiful about the silence on the street. The infrastructure of the city was exposed and sounds from blocks away suddenly became audible in a way they normally wouldn’t be. Do you think the last year has revealed an aspect of the world we were not aware of, or just reinforced something we knew was always there? Over the past twenty years we have lived through a number of catastrophes - starting with 2001, then the Iraq Invasion, the global economic crash, Trump and Brexit - and now Covid. I think the problem is that they came at a time when all politicians - from both left and right - had given up on giving you positive visions of the future. Instead they just promised to keep things stable. It meant that when the catastrophes hit it seemed to confirm the lurking idea that the future will always be dark and frightening because there was nothing positive to counter it with. And out of that came a dark pessimism - a feeling of inevitability. That there is little governments can do to stop the bad stuff. I have a hope that the experience of Covid may change that - because in both Britain and America collective action and the extraordinary achievements of modern science have shown that you may be able to solve the crisis. And out of that may come a new broader idea that we can change the world for the better. That said though - what the crisis has also revealed is the extraordinary inequality between the rich western societies and much of the developing world. The horror of what is happening in India and Brazil will have effects that we cannot predict. But they may also lead to a realisation that that relationship between the different societies across the world should also change. I hope.

I wanted to ask you about the way you use music to create contradiction or counterbalance in your films. You’ll often use an upbeat pop song to offset ominous, violent or otherwise disturbing footage. I often think about this relationship within a piece of music itself, and applied this principle quite a bit on the new record. What about this tension makes it so immediately and incredibly potent? I’m wondering about your process in designing your soundtracks? I always have a problem when film makers use music in a literal way. Pink Floyd’s Money to illustrate Bankers and greed for example. I look to music to do something different - to create a mood that helps people look differently at the stories and events I am narrating. And that often works by using music that surprises. Film and TV has become very rigid in the different forms of films it makes - so the viewer is very used to those forms - I think I try and sometimes fight against those expectations by surprising you with a song that expresses the mood I am trying to create but also makes you look with fresh eyes at the story.

In your work, you’ve looked at how the past haunts the present. Nostalgia is the style of our time. The strangeness and complexity of the moment is perhaps too much for anyone to handle so instead of thinking about the new, we celebrate and fetishize the old and outsource the rest to technology. Despite being mired in nostalgia, our culture seems to be increasingly obsessed with youth. Do you see this as a contradiction or part and parcel of the same tendency? I think there are two reasons - both related to the rise of the individual and the focus on peoples inner feelings. That spread from consumerism to politics - and in the 1990s, starting with Clinton and Blair, politicians gave up on the idea of dramatic ideas of changing society. They didn’t tell grand stories any longer. Instead they became like managers who would read, through focus groups, what individuals wanted (especially the swing voters) and give it to them. But the problem with not telling stories about the future is that the only way to go is back into the past. And I think that lack of narrative is one of the driving forces behind the contemporary nostalgia.

The other is that the in the age of the individual the problem is - how do you deal with the fact of your own mortality? In the past when you could be part of different collective groups - like political parties, churches, trades unions - which meant you could feel part of something that would go on past your own death. I have always thought that the real function of religion is to give consolation in the face of the fear of your own obliteration. Without that consolation you are frightened - and to hide from that fear you constantly go back into the past to try and hang on to what was then, and hold it close. And you fetishise the idea of youth. Because somehow, maybe that makes you immortal.

Besides recording in New York during lockdown, I also went through material I had collected from my travels to various parts of the world over the last several years. Maybe it was some sort of compensation for the lack of movement and lack of connection we were all feeling at the time. Do you think we will snap back to the globalism we saw before the pandemic or are we headed toward a new localism or nationalism? Good question. But I don’t think anyone knows. I think there are big questions to be asked about the globalism that rose up over the past thirty years. That maybe it wasn’t the west’s lifestyle and consumerism and better technology that brought down the Soviet Union - which is what the globalists argue. Maybe it was really the forces of nationalism and localism that had survived under the surface of that other global experiment. Communism.

![]()

So many of the arcs running through Can’t Get You Out of My Head specifically and your body of work in general come back to the failure of the stories we’ve been told by our elites and their institutions. In light of this, do you think a solidarity that transcends the symbolic is possible in a time of such intense atomization? Is there anything beyond this individualism? I think the politics of the future will be one that squares the circle. There is no way that you can put individualism back in the box. It is here to stay. But there is also a great yearning for radical change. It rises up in different form - from Occupy and the Arab Spring - to Corbyn in Britain. But also, don’t forget - in Trump and Brexit. They all in different ways are signs of a dissatisfaction with a political and social system that seems stuck. But to achieve radical change what you will need is a new form of collective power - because that is what really gives politicians and reformers the power to stand up against entrenched unelected elites, and to change things. So the new politics will have to be one that on the one hand allows millions of people to still carry on feeling they are self-expressive individuals, yet at the same time also feel they are part of something grand and powerful whose achievements will go on past their own death. I have a theory that the internet in its original utopian form could possibly be the architecture to build something like that. But to do that you will have to seize back control of the internet from the venture capital groups and the banks who got hold of it in 2001 - and have turned it into a narrow, deracinated form of the the original idea.

I’ve heard you talk about your skepticism toward the term “neoliberalism”; I feel the same way about the term “postmodernism.” To me, a term like this points to our present inability to relate to the future. We can only exist relative to modernism, that is, to the past, so our only creative recourse is endlessly remixing or collaging it. Can culture survive without a unifying narrative or myth? Yes. They are both terms that in effect say we are living with the ghosts of the past. And I think that has a terrible effect. Because the truth is that the economic and social system that rose up in the west from the 1980s onwards is something very different and far stranger that what “neoliberalism” implies. It is actually something new which we really haven’t fully understood yet. But because we bow down to the academics and think tank people who use those terms, we fail to do what is actually necessary - which is to develop a language and a journalism and a politics which is capable of really describing the society in which we are living to day. A narrative that allows people to really understand this strange new kind of world that is all around us. I think that is what journalism could and should do - and if it did it in a dramatic and powerful way that grabbed peoples’ imaginations then it could become strong and powerful and inspiring again. Instead we are trapped by a strange nostalgia invented by lazy academics.

What would people be surprised to learn you listen to in your spare time? Penelope Scott.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The other is that the in the age of the individual the problem is - how do you deal with the fact of your own mortality? In the past when you could be part of different collective groups - like political parties, churches, trades unions - which meant you could feel part of something that would go on past your own death. I have always thought that the real function of religion is to give consolation in the face of the fear of your own obliteration. Without that consolation you are frightened - and to hide from that fear you constantly go back into the past to try and hang on to what was then, and hold it close. And you fetishise the idea of youth. Because somehow, maybe that makes you immortal.

Besides recording in New York during lockdown, I also went through material I had collected from my travels to various parts of the world over the last several years. Maybe it was some sort of compensation for the lack of movement and lack of connection we were all feeling at the time. Do you think we will snap back to the globalism we saw before the pandemic or are we headed toward a new localism or nationalism? Good question. But I don’t think anyone knows. I think there are big questions to be asked about the globalism that rose up over the past thirty years. That maybe it wasn’t the west’s lifestyle and consumerism and better technology that brought down the Soviet Union - which is what the globalists argue. Maybe it was really the forces of nationalism and localism that had survived under the surface of that other global experiment. Communism.

So many of the arcs running through Can’t Get You Out of My Head specifically and your body of work in general come back to the failure of the stories we’ve been told by our elites and their institutions. In light of this, do you think a solidarity that transcends the symbolic is possible in a time of such intense atomization? Is there anything beyond this individualism? I think the politics of the future will be one that squares the circle. There is no way that you can put individualism back in the box. It is here to stay. But there is also a great yearning for radical change. It rises up in different form - from Occupy and the Arab Spring - to Corbyn in Britain. But also, don’t forget - in Trump and Brexit. They all in different ways are signs of a dissatisfaction with a political and social system that seems stuck. But to achieve radical change what you will need is a new form of collective power - because that is what really gives politicians and reformers the power to stand up against entrenched unelected elites, and to change things. So the new politics will have to be one that on the one hand allows millions of people to still carry on feeling they are self-expressive individuals, yet at the same time also feel they are part of something grand and powerful whose achievements will go on past their own death. I have a theory that the internet in its original utopian form could possibly be the architecture to build something like that. But to do that you will have to seize back control of the internet from the venture capital groups and the banks who got hold of it in 2001 - and have turned it into a narrow, deracinated form of the the original idea.

I’ve heard you talk about your skepticism toward the term “neoliberalism”; I feel the same way about the term “postmodernism.” To me, a term like this points to our present inability to relate to the future. We can only exist relative to modernism, that is, to the past, so our only creative recourse is endlessly remixing or collaging it. Can culture survive without a unifying narrative or myth? Yes. They are both terms that in effect say we are living with the ghosts of the past. And I think that has a terrible effect. Because the truth is that the economic and social system that rose up in the west from the 1980s onwards is something very different and far stranger that what “neoliberalism” implies. It is actually something new which we really haven’t fully understood yet. But because we bow down to the academics and think tank people who use those terms, we fail to do what is actually necessary - which is to develop a language and a journalism and a politics which is capable of really describing the society in which we are living to day. A narrative that allows people to really understand this strange new kind of world that is all around us. I think that is what journalism could and should do - and if it did it in a dramatic and powerful way that grabbed peoples’ imaginations then it could become strong and powerful and inspiring again. Instead we are trapped by a strange nostalgia invented by lazy academics.

What would people be surprised to learn you listen to in your spare time? Penelope Scott.

Eli Keszler’s new album, Icons, builds upon fragments of American abstraction, dreamlike ancient melodicism, industrial percussion, jazz age film noir and imperial decay. The music takes on forms difficult to describe outside an articulation of the loss and wonderment that defines our age.

Can’t Get You Out Of My Head is the latest film by Adam Curtis. Told across six episodes exploring love, power, money, ghosts of empire, conspiracies, artificial intelligence – and You. The work charts an “emotional history of the modern world”.